Content warning: discussions of trauma

In this second post on trauma in the books we’ve read this semester, I’m going to address Stuck Rubber Baby. There is already a post on this blog on trauma in Stuck Rubber Baby, but I’ll be addressing a different scene and approaching the story from the perspective of how literary devices portray the trauma and how accurate that portrayal is, while the previous post addresses what different parts of the drawings communicate about Toland’s experience.

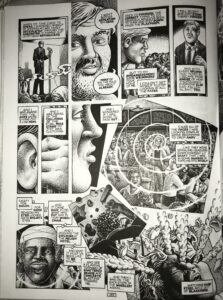

There are multiple examples of Toland describing trauma in Stuck Rubber Baby, most of which revolve around the night that he discovered his friend Sammy’s lynched body hanging from a tree. For instance, towards the end of the book, Toland is on stage at a celebration of his friend’s life, trying to give a speech in honor of Sammy, when he has a flashback of sorts on stage. The story goes from a typical narrative, with evenly spaced panels that focus on the themes of the story, to choppy and blended panels that focus on specific sensory images. For instance, as the trauma spiral starts, the pictures zoom in on Toland’s hand and ear, making readers feel disoriented. We’re used to having a contextualized narrative to help us understand the story, but all of a sudden, context is pulled out from under us, and we start to experience the story through sensory stimuli, just like Toland does.

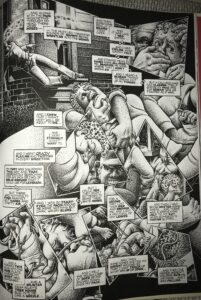

As the panels progress, they become increasingly jagged and begin to overlap with each other, until on page 191, all we see are blended fragments and the narrative falls apart. Each image is separate from the others, yet the way they’re drawn, in pieces, gives us a sense of confusion, overwhelm, and an incomplete understanding of what has happened. Like gazing into fragments of a shattered mirror, each image reflected back at the reader is distorted and incomplete, communicated only in sharp sensory snapshots, away from the context. These snapshots are presented in a confusing, overwhelming jumble, all at once and without sequence. There is no longer a neat, linear story being told; rather, Toland is remembering broken fragments and sensations, with no sense of time or space — just suffocating emotion and feelings

This portrayal of how traumatic memories are experienced is not only compellingly and effectively communicated through art — it is also startlingly accurate. Traumatic memories are encoded differently than typical narrative memories because of the sudden flood of stress hormones that kick in in an overwhelming circumstance. According to an article about traumatic memory, “When the hippocampus is in this fragmented mode, it encodes (converts) fragments of sensory memory without contextual details. … Sensation, emotion, behavior, and conscious awareness, which are usually integrated with one another, can be disconnected from their context in time and space.” This is exactly what powerfully Howard Cruse communicates in these few pages. He gives the readers some glimpse into his mind and memory, which are so altered by trauma.

In the end, if reading this sequence of events in the story leaves readers confused and overwhelmed, it’s doing its job well. Like in Nat Turner, Stuck Rubber Baby helps readers enter into and understand traumatic experiences and memory. Through art, the authors of these graphic novels communicate the way trauma changes the way people experience and recall the world around them. By tapping into two core truths of trauma — the way trauma is removed from language and the way it is encoded in a fragmented, overwhelming way — these stories allow readers to empathize and understand traumatic experiences better.