After reading Will Eisner’s A Contract With God, I was intrigued by his art and typography style, and curious about his earlier works. During my research, I came upon an image that stuck with me: a title page from Eisner’s The Spirit, a sixteen-page insert in the Sunday newspaper that ran for twelve years.

What I find so interesting about this page, in addition to the imposing figure of the masked man and the drama-filled scene depicted at the bottom of the image, is the incorporation of algebra underneath the title. (Cue movie trailer voice), “three thieves, treasure, and greed equals…,” (cue sound effect), “SPLAT!” The equation is dramatic, and (to me) funny in its incongruity. One wouldn’t normally associate math equations with tales of heroism and adventure, and yet here it is, right next to the Spirit himself’s intense masked stare. My interest in this page led me to look more into Eisner’s other title pages.

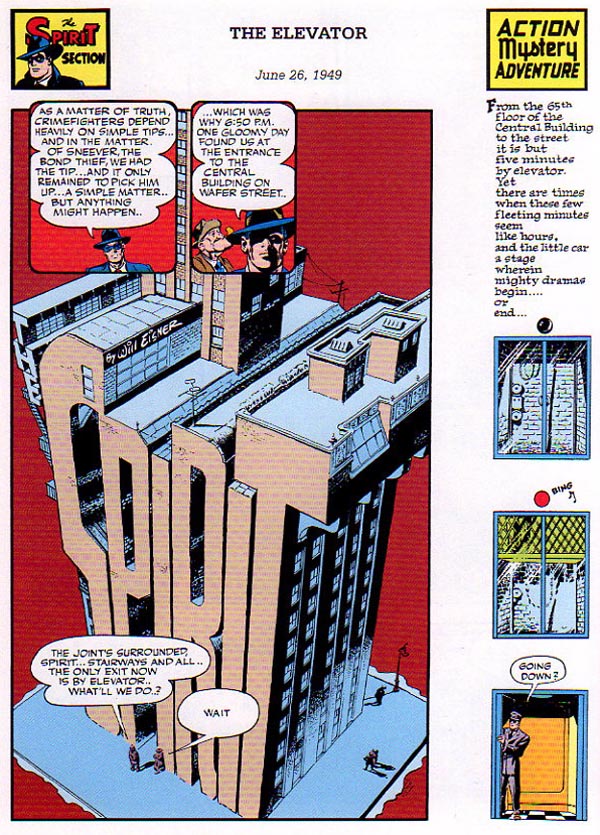

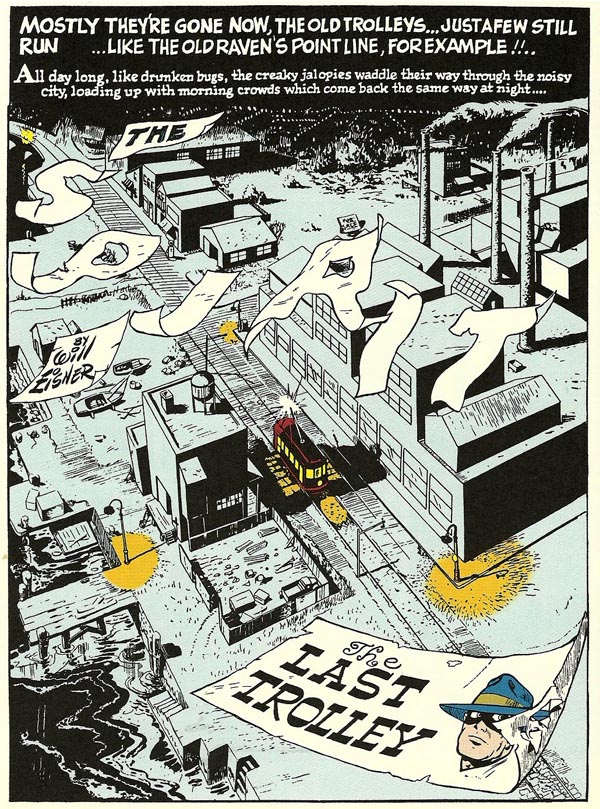

As I continued to sift through images of Eisner’s title pages, I came across more from The Spirit that I was drawn to. In the image above, the letters of the title are designed to be part of the story of the image as a building, and in the image below, they are designed as bits of paper blowing in the wind above the trolley line.

The image to the left reminded me of the chapter in A Contract With God called “The Street Singer,” in which the title is included in the image as paper falling from the windows down to the street singer’s hat.

I’ve always been interested in how titles and subtitles work to connect to the stories that they name, and the way drama and art are intertwined in Eisner’s title pages is something I find particularly interesting about his work. His penchant for blending titles into images is a lot more interesting than simply having them superimposed on top. Not only does it show an impressive artistic talent, but it helps to convey the tone of the image it is incorporated into even more clearly. If Eisner had just included his titles in the upper left-hand corner, in Times New Roman, with no algebra, would they have served their purpose equally as well as they do now? Yes. “A rose by any other name would smell as sweet,” after all, and we still would have understood them to be naming the works they’d be attached to. But would they have been as effective at conveying the tone of the image as well as the tone of the subsequent story? Definitely not!